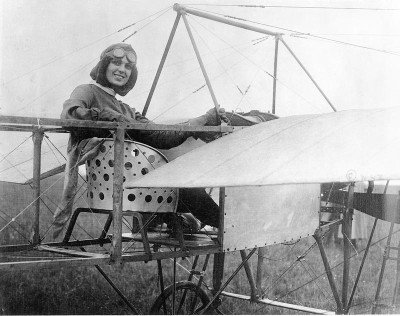

On August 1, 1911, an accomplished journalist and film screenwriter became the first female in America to receive a pilot’s certificate.

Harriet Quimby was born in May of 1875 to a poor farm family in Coldwater, Michigan. Growing up, her mother encouraged her to believe she could succeed in any almost any endeavor she dreamed of. With this in mind, she disregarded the social norms of marriage and sought out a career for herself.

Her public life began in 1902 as a writer for the San Francisco Dramatic Review and contributor for the Sunday editions of the San Francisco Chronicle and San Francisco Call. This alone set her apart from her female peers, however, she did not stop there. In a time were automobiles were scarce, she could be seen driving her yellow car around town and to the office. In her journalistic career, she was one of the first female writers to use a typewriter. The ambitious Quimby moved to New York to become a drama critic and editor of the women’s page for Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly in 1903. It was not long before she was writing feature articles for the magazine.

It wasn’t until late 1910 that her love for aviation sprouted. She attended the Belmont Park Aviation Meet, a nine day event that featured aerial races and contests of duration, distance, speed, and altitude, that took place in Elmont, New York. She became enthralled by airplanes and wanted to learn to fly as soon as possible. In her pioneering nature, she asked John Moisant, the winner of the Statue of Liberty Race, to teach her to fly. Unfortunately, before she could start lessons with Moisant at his flying school in Long Island, he died in a plane crash at an aviation meet in New Orleans.

Although a setback, it was only temporary for Quimby. Quickly and fearlessly, she began lessons with Moisant’s brother, Alfred. Her passion for flying became solidified and she ambitiously worked towards her pilot’s certificate. Her determined mindset showed when after only four months of training she officially applied for her certification.

To earn her license, the criteria was that she had to land her plane within 100 feet (30 meters) of where she left the ground. On her first attempt, she fell short but, without hesitation she tried again the very next day setting her aircraft down seven feet and nine inches (2 meters and 23 centimeters) from the mark. Thus, qualifying her for the desired license and making her the first American woman with a pilot’s license.

The new aviatrix almost immediately tried to capitalize on her new accomplishment. Due to her petite nature and fair complexion, the press deemed her the “Dresden China Aviatrix” or “China Doll” while making her professional debut in a night flight over Staten Island while touring with Moisant International Aviators. As one of the few female aviators within the U.S. it comes to no surprise, she got a lot of attention and drew crowds at any meet she was attending.

Just because of her new found fame, she did not stop writing, her focus just changed. For example, many of her articles pertained to how she learned to fly and the dangers that came with it. She also preached at how aviation could be an ideal sport for women.

Quimby continued her adventures with aviation in 1911 by deciding she wanted to cross the English Channel. Advised by Gustav Hamel, who was actually unsure of a women’s ability to accomplish such a flight and offered to disguise himself as her and do it for her. She strongly declined and embarked on the 25 mile (40 kilometers) from Dover, England, to Hardelot, France. She was an instant sensation, however, her front page fame was covered due to sinking of the Titanic.

Her love for aviation never waivered throughout her career afterward, continuing to compete in air meets. Unfortunately, her passion would be her ultimate demise. On July 1, 1912, she was performing in the Harvard-Boston Aviation Meet with her Bleriot Monoplane. The plane suddenly pitched forward, throwing her passenger, William Willard, out of his seat. Her plane then flipped over throwing her out as well. The pair fell to their deaths, leaving crowds horrified, in the Dorchester Harbor.

After 80 years, Quimby received the recognition she deserved for her crossing of the English Channel. The U.S. Post Office generated a commemorative 50 cent stamp that honors her chapter of aviation history and accomplishments.

Written by Samantha Yost

Published on 8/1/2025